Jan

2022

For many people, their image of meditation involves sitting with a spiritual pose in yoga pants and being blissed out in the present moment in a temple that is both under a waterfall and on top of a mountain. Throw in some reincarnation, enlightenment, universal love, and Oneness, and things are getting really meditative. And incense. You can't meditate without incense...

There is some truth behind this popular image — or, at least, I believe there is. For instance, I think meditation can in fact help bring you closer to enlightenment, and I think it is possible to understand what that means without getting caught up in nonsense. However, in this post, I want to answer our question of what meditation is and why it is a good thing to do in a way that doesn't involve any of that spiritual stuff.

To give you a sense of what this explanation looks like, it helps to think of meditation as like physical exercise. Just as there are different kinds of physical exercises, there are different kinds of meditative practices. Some are like strength training, some are like cardio, some are like stretching, and so on. Each kind of meditative practice has different cognitive benefits associated with it, and these can be measured and objectively verified — just as you can verify that lifting weights makes you stronger or that stretching makes you more flexible.

Moreover, just as physical exercise improves the quality of your body, meditation improves the quality of your mind. There is growing evidence that meditation helps prevent and treat a variety of mental health problems, such as depression and anxiety. However, the point here is more general than that. Just as there is more to physical exercise than being effective against type 2 diabetes, there is more to meditation than preventing or treating mental health problems. Meditation can help you become more mentally athletic.

If all of this is true, then why doesn't everyone meditate? There are many reasons, and people are different. The analogy with physical exercise is useful again: even though most people agree that it is a good thing to do, they don't exercise as much as they would like to. So, part of the explanation is weakness of will. Another part is a lack of education and awareness — some people don’t know of, or fully appreciate, the benefits of exercise. These sorts of explanations apply to meditation as well.

However, there is another explanation that I think is special to meditation: unlike the body, the mind is invisible. It is easy to see when you gain weight — the number on the scales goes up, your clothes don't fit as well, etc. What is the mental equivalent of seeing that you have gained weight? Or to frame it more positively: what is the mental equivalent of seeing that you have become stronger, fitter, more flexible, etc.? It is not impossible to notice these changes, but they are less obvious than the corresponding bodily changes that result from exercise. Because of this, the positive feedback we get from meditation is less obvious, and so there can be less motivation to do it.

So to get started, let's look more carefully at the mind so we can see the sorts of changes — and benefits — that meditation may bring about. In particular, we're going to focus on attention. The reason for this is threefold. First, attention is a crucial part of the foundation for human cognition, and so any improvement to it is going to have far-reaching implications. Second, many meditative practices focus specifically on the training of attention. Third, attention is well-studied by cognitive psychology, and so we should be able to acquire scientific evidence that confirms (or disconfirms) any benefits that meditation has on it. These three motivations correspond to the next three sections.

Attention

There's an important fact about attention that most of us are unaware of: it may not seem like it, but we have very little control over how we allocate our attention.

Although we are living in an attention economy and attentional disorders are on the rise, these are not what I mean when I say that we have little control over our attention. Even in ideal circumstances, the best of us are still are easily distracted. Consider a friend of yours who doesn't have any apparent attentional deficit symptoms, and imagine them in a quiet place away from all of their usual digital distractions. That person in that ideal situation will still have little control over their attention.

In The Principles of Psychology, William James stated this observation particularly forcefully:

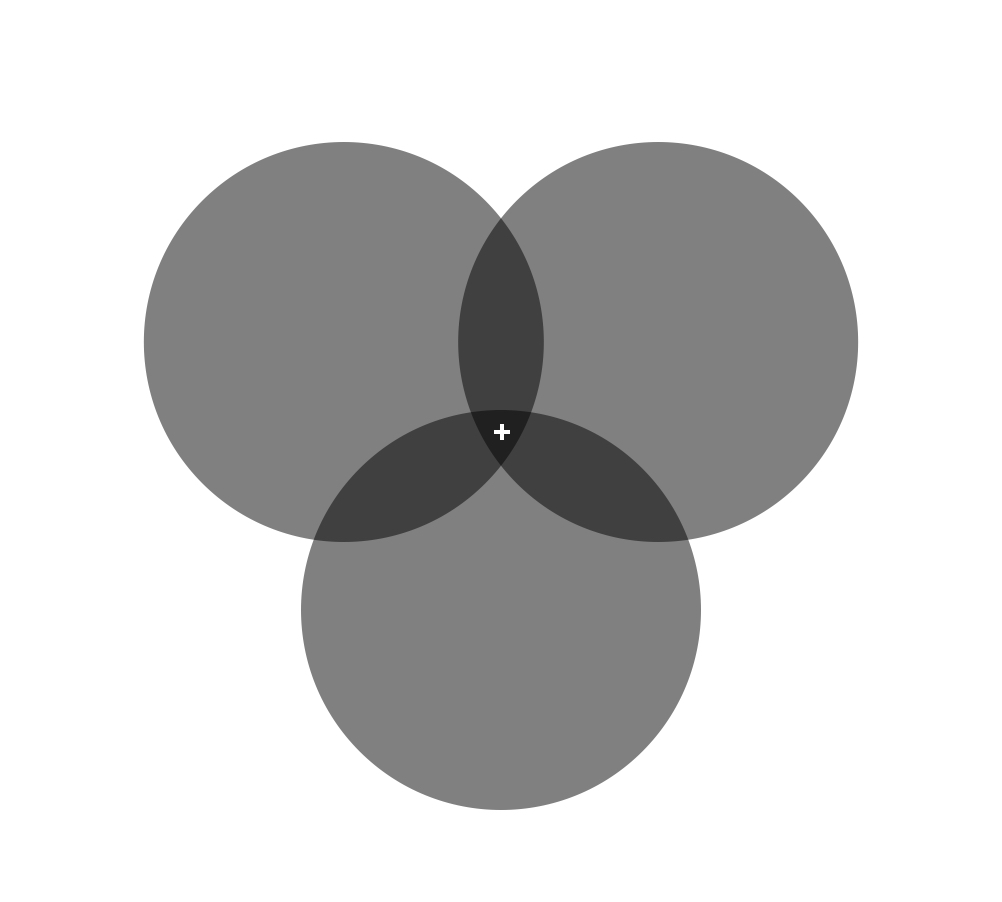

Take a look at the three grey discs below, and focus your gaze on the white cross at the center of their intersection. Now, without shifting your eyes, direct your attention to the bottom disc. Something interesting should happen: it will appear slightly darker than the other discs. Now shift your attention to one of the other discs... now that disc will appear slightly darker.

This example is due to Tse 2005 and it demonstrates one way in which our attention affects our perception. Roughly speaking, focusing attention on an object increases its apparent contrast (the full story is more complicated than this, but that is the basic idea).

That attention affects our perception in this way is an important thing to know, but this example also demonstrates an even more important point about attention. Take a look at the discs again, and this time try to stay focused on the bottom disc for long as possible (while keeping your gaze fixated on the white cross). Like before, the disc will appear darker. But this time you can notice something else: soon after the bottom disc appears darker, one of the other discs will suddenly appear darker. This happens even though you are trying to keep your attention focused on the bottom disc. This is your attention wandering.

Notice how quickly your attentions shifts its focus and how little ability you have in preventing it from happening. In fact, try this as a meta-task: pay attention to your attention wandering. What is the invisible force that moves your attention away from the bottom disc? It's not you since you are trying to stay focused on the bottom disc. And it isn't the discs themselves since they are completely static. If one of the discs started flashing, for instance, that would naturally explain why your attention shifts to it. But that is clearly not happening.

One explanation for why your attention wanders in this way is that this is your brain's way of searching the environment for new and valuable information. One may even argue that this search procedure is optimal in some sense — perhaps for the typical environment our ancestors found themselves in. Having one's attention wander somewhat randomly, scanning the environment, can be a good way to spot novel sources of food, hidden dangers, etc.

However, success for us involves tasks that are very different from that of our ancestors. Just as our natural predilection for calorie-dense food once served an evolutionary purpose but is now maladaptive, something similar appears to be the case with an attention that wanders. Success in today's world often requires extended periods of deep concentration. For example, suppose you are in a quiet library studying for an important exam. Your success on the exam depends, in part, on your ability to sustain a state of focused attention on your study materials. However, even in this seemingly ideal environment, you still have a limited ability to stay focused in this way. People vary, of course, but generally speaking everyone's attention eventually wanders — and more than we realize. And it seems that all we can do — beyond minimizing distractions — is catch our attention as soon as it wanders and then bring it back to our choice of focus.

Studying for an exam is just one particular kind of example, but so much of our success depends on our ability to control our attention in this way. As before, William James put this point in a particularly forceful way:

In fact, there is more to this problem than simply keep our attention focused on something. Our success is also heavily dependent on our ability to change the focus of our attention. Just as our attention naturally wanders seemingly on its own accord, it also has a tendency to fixate. For example, it has been shown that anger and conflict have a strong tendency to focus our attention, and it is difficult to "switch gears" and focus on something else immediately afterwards. In other words, our attention also has an inertia to it. This inertia can become pathological, for example by taking the form of excessive rumination or addiction. However, even when it isn't pathological, our attentional inertia is often suboptimal — at least for the sorts of environments we now find ourselves in.

In addition to being able to shift the focus of our attention from one thing to another, our success also often depends on our ability to change the focus of our attention in another way: by expanding it. This is also sometimes called diffusing attention. The basic idea is that we often need to "zoom out" and take a larger perspective on things. We've all seen someone be obsessed about the details of something and unable to take a step back and look at the bigger picture. This inability to expand the scope of one's attention often leads to futile work and lost opportunities. It's another way in which we can lack control over our attention.

So we have seen three ways in which we can lack control over our attention: focusing it, shifting it, and diffusing it. The better we are at controlling our attention in these ways, the better we do in general. The problem is that we're actually not very good at controlling our attention, and worse, it is easy to be deluded about how good we are. (Similar to how the vast majority of people think they are better than average drivers.)

This problem is an extremely important one. Attention is our brain's system for solving a fundamental problem it is constantly confronted with. The brain has limited cognitive resources and too many issues that it needs to deal with. Attention helps the brain prioritize what it spends its precious resources on. As such, attention is a core part of the foundation for all of human cognition. So it is a pretty major problem if we have poor control over it — even in ideal environments (the quiet library), let alone those filled with digital distractions.

In fact, it is difficult to think of a problem that is more foundational, more widespread, and which would have more profound and wide-reaching benefits if we could solve it. All of our other problems would be much more easily solved — or even immediately solved — if we could solve the attention problem.

That may seem like an overstatement, but it isn't. The reason why is that our ability to solve any problem is determined by how effectively we can use our tiny brains to navigate and interact with the world, where so many of our problems are located — climate change, racism, inequality, pollution, disease, etc. If your attention is degraded, your ability to solve any other problem is also degraded.

However, in order to solve this problem of attention, we would need James' education par excellence. That is, we need some practical method for systematically improving our control over our attention. Enter the practice of meditation...

ONLINE COURSE

Meditation x Critical Thinking

Learn how to improve the quality of your thinking using the practice of meditation combined with the principles of critical thinking.

ONLINE COURSE

Meditation x Critical Thinking

Learn how to improve the quality of your thinking using the practice of meditation combined with the principles of critical thinking.

Meditation

There are many different ways to practice meditation and their effects on the mind can vary substantially. To keep things simple, I'll focus on two particular forms of meditation that have fairly straightforward effects on our attention. These two forms of meditation have come to be known as: focused-attention meditation, and open-monitoring meditation. Roughly speaking, these two meditative practices help us learn to do two different things to our attention: to focus it, and to diffuse it. As we will see in a moment, they also help us learn how to control our attention in others ways as well. However, for the sake of getting started, it helps to think of these practices in this coarse-grained way: focused-attention meditation helps us focus our attention, and open-monitoring meditation helps us diffuse it.

Let's look at each practice in more detail...

The instructions for focused-attention meditation vary, but a typical set goes something like this:

It can also be challenging to notice when your attention has wandered. In the case of the grey discs, it is easier to notice because you have a visual cue for when your attention has wandered: one of the other grey discs becomes darker. However, in focused-attention meditation, there is no visual cue, and it is easy to become lost in a stream of thoughts without realizing it for quite a while.

Another difficulty that many people experience with this form of practice is that it can be frustrating precisely because the task seems so simple. It is common to feel that you should be able to hold your attention on your breath for long periods of time. As a result, it is easy to become frustrated with the practice and eventually dismissive of it. It is part of the practice to be okay with the fact that your attention wanders — even though you are trying to keep it focused.

Okay, so why practice this form of meditation? What benefit should be expected?

There are many benefits, but a primary one is that you get better at focusing your attention. Just as you get better at anything the more you practice it, the more you practice focusing your attention, the better you get at doing exactly that. It's also a bit like going to the gym in that the more you practice lifting heavy weights, the better you get at lifting heavy weights. Metaphorically, the practice of focused-attention meditation develops the muscle in your mind that focuses your attention.

There is also a cluster of other benefits that are somewhat secondary to this primary benefit.

In addition to becoming better at focusing your attention, you also get better at keeping your attention still. These might sound like they are the same thing, but they are different: keeping your attention focused is just one way of keeping your attention still. As we will see in a moment, keeping your attention diffused is another way of keeping your attention still. Metaphorically, the practice of focused-attention meditation also develops the core muscles of your mind that enable you to keep your attention stable.

Another secondary benefit is that you get better at noticing when your attention has wandered. This is a metacognitive ability that has a range of benefits, from emotional regulation, to executive control over behavior, to better decision making. Each time your attention wanders away from your breath and you become absorbed in some train of thought, you enter a daydream. It's been estimated that we spend almost half of our time daydreaming and that this tends to make us unhappy (Killingsworth and Gilbert 2010). There are, however, some benefits to daydreaming — especially a particular form known as positive constructive daydreaming — but the key is to have control over whether or not you are daydreaming (McMillan et al. 2013). We practice this skill during focused-attention every time we notice that our attention has wandered and choose to shift our focus back to our breath. Continuing with our physical exercise metaphor, the practice of focused-attention meditation develops your mental coordination, so that your attention flows smoothly and efficiently to what you choose.

There is much more to say about focused-attention meditation, but let's now take a look at open-monitoring meditation. As with focused-attention meditation, the instructions can also vary, but a typical set of instructions goes as follows:

A common challenge that one encounters with open-monitoring meditation is that the kinds of thoughts that emerge tend to be both novel and significant for you. This makes them especially good at grabbing your attention. For example, you may suddenly remember your new year's resolution that you never got around to doing. Or you may realize that your job is making you unhappy and that it is time to find a new one. These thoughts tend to be those that are lurking around in the back of your mind but which never fully make it into your awareness.

One reason why they remain lurking in the back of your mind is because you normally don't have enough spare attention to bring them into the foreground of consciousness.1 As a result, when you practice diffusing your attention during open-monitoring meditation, suddenly these thoughts are able to move a little bit more into awareness. And since they tend to be important to you, there is a natural tendency for you to focus on them.

This process of novel and significant thoughts suddenly appearing in your awareness is experienced as an insight — an "ah ha!" moment. When the thought is especially novel and significant, it may even have a "eureka!" feeling to it. These insights can be about anything. They can be personal in nature, they can be about other people and relationships, they can be about some problem you are working on, or they may even have a philosophical or spiritual element to them. Some of these insights can be very valuable, even life-changing. However, the goal during open-monitoring meditation is to keep your attention diffused. This makes the practice challenging: on the one hand you don't want to lose these insights, but, on the other hand, the point of the practice is to not focus attention on them. To make matters worse: the better you get at diffusing your attention, the more novel and significant the insights become.

As a side note: a common form of meditation that is a mixture of focused-attention and open-monitoring is called vipassanā meditation. The literal translation of vipassanā (a Pāli term) is "special or super seeing", and a common translation is "insight". So vipassanā meditation is insight meditation, and there is a long tradition of using this practice to cultivate insight (and in particular the insight that corresponds to enlightenment, but that is a topic for another discussion).

In describing this common challenge with practicing open-monitoring meditation, we also see one of its benefits. By practicing the skill of diffusing your attention, you get better at diffusing your attention. Continuing our analogy with physical exercise, we can think of this as a kind of stretching of the mind. The more you stretch, the more flexible your mind becomes. And the thoughts lurking in the back of your mind are like your toes: by becoming more flexible it becomes easier for you to touch them. Obviously, there is more to flexibility than being able to touch your toes, and the same is true for mental flexibility: it is not all about insights. For example, by getting better at diffusing your attention, you get better at defocusing it from one thing and refocusing to another completely unrelated thing.

As with focused-attention meditation, there are other benefits to open-monitoring meditation. For example, you also get better at keeping your attention still. By learning how to maintain a diffused state of attention, you develop the complementary core muscles that maintain your attentional balance.

You also further develop your meta-cognitive skills. In addition to getting better at noticing when your attention has wandered, you get better at noticing your current thoughts and sensations — and how they drive your behavior and decision making. This introduces new possibilities for improving your behavior and decision making. By becoming aware of the hidden drivers behind your actions, you get a chance to intervene on them and make better actions instead.

Another benefit is that you get better at disengaging from a train of thought or a sensation without the need of immediately replacing it with another. As a result, it becomes easier to take moments of genuine rest during the day and to maintain a state of equanimity during periods of stress or adversity.

There is much more to say about open-monitoring meditation, as well as how it can be combined with focused-attention meditation. There is also a lot more to be said about what happens as you become more experienced with these meditative practices. The above discussion is primarily aimed at beginners (and those who are skeptical but open-minded about meditation). As such, it only scratches the surface of what meditation is about. (Those who are more knowledgeable about meditation will note that I haven't said anything about mindfulness, jhanas, duhkka, the other practices of the noble eightfold path, etc.)

However, there is one final point that should be highlighted before we move on. This is an important point and it is often neglected in discussions of meditation: the practice of meditation is not risk-free. Like any other substantial intervention on the body or mind, there can be side effects and injuries. Although there are many benefits to meditation, it doesn't follow that everyone should do it no matter what. Again, the analogy with physical exercise is helpful here. Regular cardiovascular exercise is generally speaking a good thing to do, but it is a stupid thing to do with if you have the flu. When you have the flu, you need to rest. Similarly, meditation can be a harmful thing to do if you are suffering from some mental ailment. For example, there are documented cases of intensely practicing open-monitoring causing trauma to evolve into a psychosis-like condition (Miller 1983). Adverse experiences may also occur for individuals with no previous history of mental health problems (Farias et al. 2020).

Because the instructions of meditation sound so simple, it can be easy to think that the practice has no real effect on the mind — or that the effects are only mild in nature (e.g., pleasant calming effects). Nothing could be further from the truth. If practiced diligently, meditation can have extremely powerful effects on the mind. Indeed, as I argue in my book, Psychedelic Experience, the effects of meditation can be similar in important respects to those of psychedelic drugs. So it is wise to approach meditation with some caution and be mindful that it may have unexpected effects.

So long as we keep this important qualification in mind, then I think it is fair to say that the practice of meditation is generally of great benefit (like physical exercise). In particular, focused-attention and open-monitoring meditation can bring us a long way with respect to James' education par excellence.

Now that we have an idea of what meditation is why it is a good thing to do (generally speaking), let's take a look at some of the scientific evidence in support of this claim.

ONLINE COURSE

Meditation x Critical Thinking

Learn how to improve the quality of your thinking using the practice of meditation combined with the principles of critical thinking.

ONLINE COURSE

Meditation x Critical Thinking

Learn how to improve the quality of your thinking using the practice of meditation combined with the principles of critical thinking.

Scientific evidence

There is now a large body of scientific evidence demonstrating that meditation has a variety of beneficial effects on attention. For the sake of brevity, I will focus on one particular thread of the research that involves the phenomenon of attentional blink and how its modulated by the practice of meditation.

Let's begin with a quick primer on the attentional blink phenomenon. Suppose you have the following task to perform. You are presented with a rapid sequence of letters and somewhere in this sequence of letters, there is a white letter and an 'X'. Your task is to press a button when you see either the white letter or the 'X'. You can get a feel for how this works by watching the video below.

What is interesting about this task is that if the 'X' appears within about half a second of the white letter, most people fail to notice it.

The standard explanation for why this occurs involves the dynamics of our limited attentional resources. The process of registering that the white letter has appeared consumes a substantial portion of your available attentional resource. And it takes some time for you to shift attentional resource from one cognitive task to another. So when the 'X' appears soon after the white letter, there isn't enough time for your mind to shift enough of its attentional resource from the white letter to the 'X''. There is, thus, a kind of lag effect in the dynamics of your attention. Because of this, you don't have enough available attentional resource to become aware of the 'X' when it appears. As a result, your subjective experience is as if you blinked right when the 'X' appears.

One side point worth mentioning is that although your subjective experience is similar to that of blinking when the 'X' appears, there is a sense in which you do perceive the 'X'. It is just that you perceive it unconsciously. There is substantial evidence indicating that although one may fail to be aware of the second stimulus, it nevertheless undergoes substantial unconscious processing — enough even to cause observable priming effects (Shapiro et al. 1997, Visser et al. 2005). In other words, the 'X' makes its way into your mind, but because it doesn't receive sufficient attention, it fails to appear in your conscious experience.

Now that we know about attentional blink, let's consider how it is affected by the practice of meditation. If the previous section is correct, then meditation should improve one's ability to allocate attentional resources efficiently, and so we should see a reduction in the attentional blink effect. Indeed, there are now several studies in support of this hypothesis.

In the first such study, Slagter et al. 2007 found that 3 months of intensive vipassanā meditation training reduced attentional blink. Participants in the study who underwent the meditation training were able to detect the second stimulus more frequently than they could before the training. Moreover, this effect was statistically significant in comparison to a matched control group.

Since this initial study, several others have found similar effects. At time of writing, these include Leeuwen et al. 2009, Fabio and Towey 2018, Roca and Vazquez 2020, and Wang et al. 2021. Two other studies have also examined potential differences between the effects that focused-attention and open-monitoring meditation have on attentional blink. Vugt and Slagter 2014 and Colzato et al. 2015 found evidence indicating that open-monitoring meditation resulted in a greater reduction in attentional blink than focused-attention meditation did. Altogether, these studies confirm the hypothesis that meditation improves our ability to allocate attentional resources effectively and thereby make it easier for one to detect the second stimulus. In short, the practice of meditation reduces the attentional blink. Said another way, by improving your control over your attention, meditation expands your awareness.

It is important to note that this is just one way in which we have observed meditation having a beneficial impact on attention. There are now numerous other studies that use different experimental paradigms and show benefits to attention. As I mentioned earlier, this literature is large and growing rapidly, so I won't review it here. For two recent reviews and meta-analyses of the effects on attention, see Sumantry and Stewart 2021 and Verhaeghen 2021. Naturally, there is some variation in the results, but overall it is becoming increasingly clear that meditation does indeed improve our ability to control our attention.

Moreover, since attention is an integral part of the foundation for all cognition, we should also expect to see that meditation has a range of downstream cognitive benefits. The evidence for this is accumulating as well. For example, meditation has been observed to have beneficial impacts on creativity (e.g., Colzato et al. 2012), memory (see Levi and Rosenstreich 2018 for a review), and better decision making (see Karelaia and Reb 2015 for a review). These benefits require a more detailed discussion, so we will leave it there for now. There is also a discussion to be had about the therapeutic benefits of meditation (Wielgosz et al. 2019). The important point for our present focus is that by improving attention, meditation also has a range of other important benefits to cognition.

Another useful way to think of the fundamental effects of meditation is in terms of what Raffone et al. 2019 call a brain theory of meditation. The basic idea behind this theory is that there are substantial energetic limitations on the brain and the practice of meditation improves the efficiency by which we use our limited cognitive resources. We can extract three basic premises in support of the theory: (i) our brains have a limited capacity for neural activity at any given moment, (ii) we waste some — and perhaps a lot — of our limited neural activity, and (iii) meditation can reduce this waste. Let's take a quick look at each premise.

The first premise is fairly straightforward, except that it may come as a surprise that the energetic limitations on the brain are rather strong. Every time a neuron fires, some energy is consumed and some waste is generated. Since we have limited energy and limited ability to clear waste (which appears to happen primarily during sleep and after exercise, Holstein- Rathlou et al. 2018), there is an upper bound on how cognitively active we can be at any given moment. Indeed, it has been estimated that less than 1% of the neurons in the cortex can be simultaneously firing at an enhanced rate (Lennie 2003). Since the brain is a finite physical system it shouldn't come as a surprise that there is a limit on what it can do, but it pays to remember this and to be aware of how tight the constraints are.

The second premise is that we waste a substantial amount of our precious neural activity. Since waste involves a value assessment, we should be careful in picking out examples (what is waste for one person is not waste for another), but we can identify some examples that will tend to be fairly common. For example, as mentioned earlier, we spend almost 50% of our time mind wandering. Most of the time this makes us unhappy (Killingsworth and Gilbert 2010) and it incurs substantial costs to cognitive task performance (see Mooneyham and Schooler 2013 for a review). Although there are some benefits to mind wandering (it can help with creativity and complex planning), these probably mostly occur when the wandering is under our control (McMillan et al. 2013). This is one example of how we may not be using our limited brain resources efficiently. Other examples include being consumed by unhelpful (or even destructive) emotions, being distracted, working towards goals that are misaligned with our values, and so on.

The third premise is that meditation can help use our limited resources more efficiently. To run with the last three examples from the previous paragraph: meditation appears to help with the regulation of emotion (Norman et al. 2014), reduces distractibility (which is a specific form improving attentional control), and increased alignment with one's values (Gregoire et al. 2012, Smyth et al. 2020). With respect to mind wandering, we also see the benefits we would expect. Several studies have shown that meditation reduces activity in the default mode network (DMN), which tends to become more active during phases of mind wandering (Tomasino et al. 2012, Brewer et al. 2011, and Garrison et al. 2015). In particular, Scheibner et al. 2017 found that during sessions of focused-attention meditation, the DMN was activated when participants were mind wandering and deactivated when their attention was focused on their breath.

Following similar reasoning, and drawing upon a large body of behavioral and neuroscientific evidence, Raffone et al. 2019 propose that one of the core features of meditation is that it improves our ability to maintain efficient brain states with a higher regulation of energy consumption (and waste generation). This is their brain theory of meditation. In particular, negative emotions and mind wandering are thought to be especially inefficient, but they can be substantially reduced and better regulated via the practice of meditation.

Thinking about the effects of meditation in this "first principles" way can help us appreciate the full generality of its benefits. It also helps explain why some people are so enthusiastic about meditation and believe that it is an integral part of the solution to almost any problem. There is some truth to this. However, we should remember that meditation is not a panacea. Just as regular exercise is generally a good thing to do, it is not a solution to all problems, it is not something we should always do, and there is always a risk of experiencing injury. Meditation is not unlike physical exercise in these respects.

Finally, another word of caution is in order. The scientific research on meditation is rapidly growing, but it is still a relatively new field, so we should be careful in how confidently we draw conclusions from it. Van Dam et al. 2018 and Davidson and Dahl 2018 give good overviews of the challenges and limitations involved in this research, especially as it relates to the mental quality of mindfulness (which is a topic that requires another article). More research definitely needs to be done, and it is still early days regarding our scientific understanding of meditation. However, the theory and evidence are both pointing in the same direction: meditation improves our ability to control our attentional resources, and this has a diverse range of other benefits that follow as a result.

In short, the theory and evidence both indicate that it is quite likely that the practice of meditation is indeed James' education par excellence.2

Conclusion

There are many different forms of meditation, and they have a diverse range of benefits. This has been a brief discussion of the benefits of two particular meditative practices: focused-attention meditation and open-monitoring meditation. These are two ways of training our attentional capabilities. They help us to better focus and diffuse our attention, to be more flexible and agile in how we shift our attention, and to be more stable in how we hold our attention. They also have a range of downstream cognitive benefits — ranging from enhanced creativity to better decision making.

The benefits of meditation to attention are important because we all have limited attentional resources and we do not use them as efficiently as we can. That means that no matter what you are trying to do — whether it be running a business, making art, raising children, or moving along a spiritual path — you will do it better if you have better control over your attention. Meditation is a simple and effective technique for developing better control over your attention.

There is much more to meditation than what I have described here, and I think there are important reasons to meditate that go beyond those involving mere attentional management. I've focused on attention here because it is so important and foundational for all human activity and because we have good scientific evidence that meditation improves attentional control. In short, even if you are entirely skeptical about the larger belief systems that are often associated with meditation, you still have a really good reason to meditate.

ONLINE COURSE

Meditation x Critical Thinking

Learn how to improve the quality of your thinking using the practice of meditation combined with the principles of critical thinking.

ONLINE COURSE

Meditation x Critical Thinking

Learn how to improve the quality of your thinking using the practice of meditation combined with the principles of critical thinking.